Retirement, GOVERNMENT THAT WORKS

NorthJersey.com: NJ public pensions face fiscal peril as new police and fire retirees grow, report says

By Dustin Racioppi

New Jersey’s pension system for public employees costs more than most other states while offering “generous” benefits that are increasingly going toward more retirees than active employees, according to a new report.

One retirement fund, for police and firefighters, had more people collecting pension benefits in 2019 than current workers, and two others were on a similar trajectory — meaning those funds are less able to handle investments risks, the analysis by the fiscally conservative think tank Garden State Initiative found.

All this is despite years of increasing payments by the state that reached a record of nearly $7 billion this year. Without making policy changes for tens of thousands of public employees, New Jersey’s political leaders will likely face difficult choices on how to use taxpayer dollars to stabilize the pension funds, the group said.

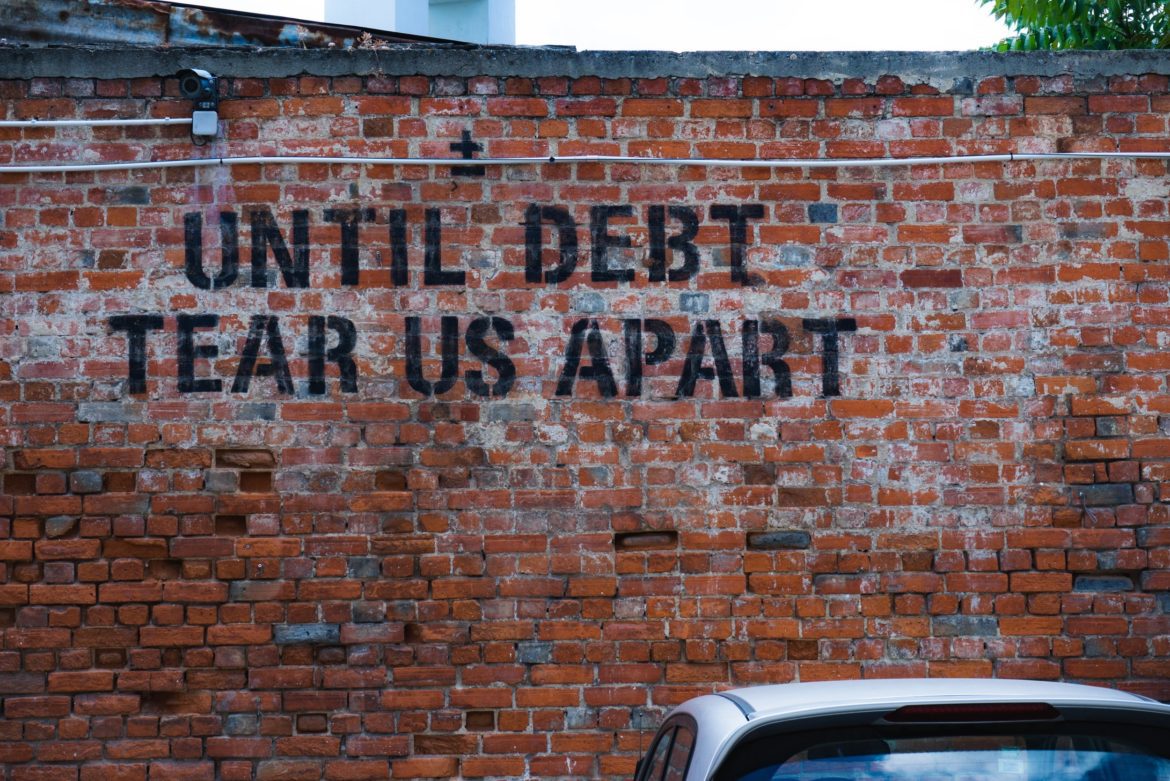

“For decades New Jersey’s pension plans for public employees have promised generous benefits without paying for them. Now the bill is coming due,” said the report’s author, Andrew Biggs, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C.

“You can’t just keep doing the things you’ve been doing,” he added.

Just about every state has problems with its pension funds for public workers, but New Jersey is in an “elite” group with strained systems that includes Connecticut, Illinois and Kentucky, Biggs said.

There is widespread agreement on New Jersey’s troubles, and it has regularly ranked among the worst-funded pension systems in the country.

The Brookings Institution said in a March analysis that the pension fund for teachers is in near-term trouble because of low investment returns and a poor funding ratio of 42%. Earlier this year the Tax Foundation ranked New Jersey 50th, using 2019 data, for having the largest deficit between its assets and liabilities.

And Murphy himself led a panel in 2005 tasked with studying the state’s pension funds and recommended similar types of reforms that Garden State Initiative does in its report, a copy of which was obtained by the USA TODAY Network ahead of its release this week.

The think tank is led by Regina Egea, a former chief of staff to Republican Gov. Chris Christie, who led pension reforms and the payment plan Murphy must follow. Murphy’s office has disparaged the nonprofit’s credibility in the past, calling it “simply a political organization.” It bills itself as nonpartisan.

The state’s poor standing on pension funding is the result of decades of underfunding by governors of both parties starting in 1996.

The state has made strides in recent years, though, with changes to benefit plans and a ramp-up of state payments into the pension fund under Christie. Murphy, a Democrat, has continued that schedule and, this year, made the biggest payment ever, $6.9 billion, thanks to strong revenues and federal stimulus funds.

But Murphy also faces a dilemma. He still has to pay $7 billion a year into the pension fund going forward — about 15% of all state spending — but can’t expect to get federal aid in the years ahead. He’s also pledged not to raise taxes in his final four-year term.

Murphy resisted pension reforms in his first term, saying nothing should be done until the state lives up to its obligation to public workers. Now that it has, though, he doubled down on his resistance to reforms such as moving employees toward a 401(k)-style plan, which many employers offer.

“While we’ve begun to change the reality of the pension crisis that we inherited, you still need to stay in there year after year and hit that full pension payment. And that’s what we’re committed to doing,” he said Monday. “We will make that full payment.”

Most of New Jersey’s public employees are enrolled in what is known as a defined benefit plan, meaning they and the state pay into funds at a calculated amount and the workers get a guaranteed payout in retirement.

That puts full responsibility on the state — or, in other cases, local governments — to cover a plan’s underfunding if investment returns come in lower than expected.

On top of that, the state pays toward its unfunded liability that has been built up over the years — in New Jersey’s case, decades. The combined unfunded liabilities of New Jersey’s public plans increased from $58 billion in 2000 to $186 billion in 2019, according to the Garden State Initiative report.

As it stands now, the state is relying on government payments and investment returns to bring the pension fund back to health, Biggs said. But poor returns risk that, he said, and the pension systems would “get worse before they get better.”

The police and firefighters fund is one example used by Garden State Initiative to illustrate the perils facing the state. Since 2001, the worker-to-retiree ratio declined from 1.8 workers per beneficiary in 2001 to 0.9 in 2019, meaning there were more beneficiaries than active employees.

The Public Employees’ Retirement System had 1.4 workers to every one retiree in 2019, and the teachers’ plan had 1.3 to each one, according to the report.

Because of that shift, the state should have become more conservative in its investments, Biggs said.

“They are clearly operating against best practices that are recommended for pensions,” he said.

“The government is hoping they can gamble their way out by taking on risk or risky investments. But because these pension plans have so many more retirees than active workers, it’s tougher for them to take on that investment risk,” he added. “They need to look beyond just propping up the current system.”